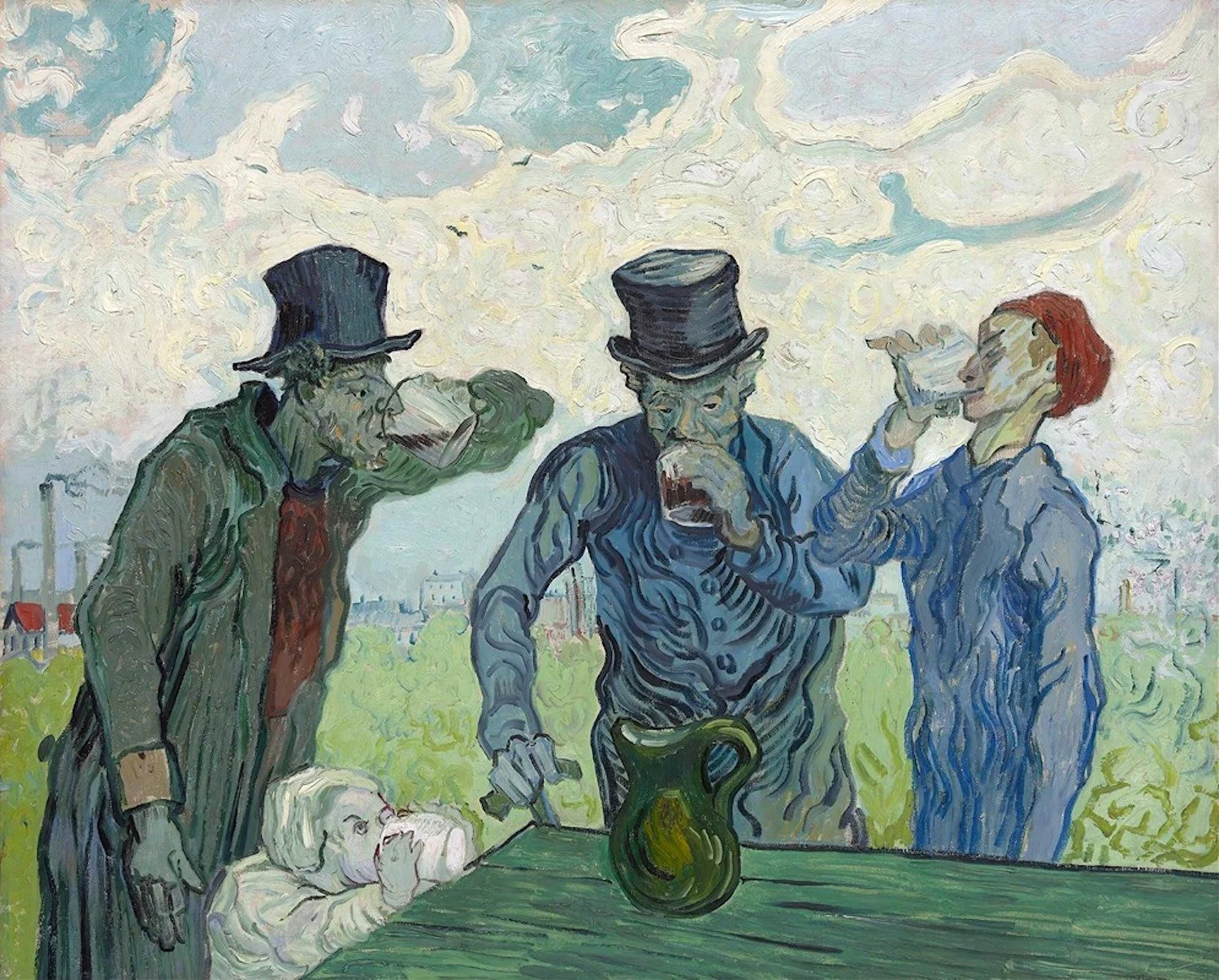

The Drinkers by Vincent van Gogh (1890)

The Wisdom of Wonder

A Guide to Life for Seekers and Curious Minds

Humans are inherently curious from birth. As soon as we start speaking, we ask questions like “Why?”—about the nature, meaning, and origin of things. This curiosity is not a defect or something to outgrow; it shows that we are creatures driven by a desire for understanding. In essence, wonder reflects a fundamental aspect of human nature: that we are all seekers.

Across different traditions, wonder serves as both the beginning and the essence of philosophy. In this essay, we will explore three main aspects of wonder: first, as the basis for philosophical inquiry; second, as a distinctive method of understanding; and third, as a spiritual or philosophical practice.

1. The Origin of Philosophy

Philosophy does not start with certainty but with wonder. The Greeks termed this amazement “thaumazein”—a profound sense of awe.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle writes:

It is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize.

For Aristotle, wonder isn't just a passive feeling; it's the driving force behind inquiry. It stimulates the mind to explore a world that is understandable but always has more to discover.

Plato echoes this idea when Socrates states:

This sense of wonder is the mark of the philosopher. Philosophy indeed has no other origin.

Wonder is not the lack of knowledge but the very condition that allows knowledge to exist. It shakes complacency and awakens the soul.

The existential philosopher Martin Heidegger elaborates on this idea in Introduction to Metaphysics, stating that wonder isn't about specific facts but about being itself: “The feeling of wonder is nothing less than the astonishment at the fact that beings are—and not nothing.”

This ontological astonishment extends beyond mere curiosity, transforming our relationship with existence.

Even in modern ethics, wonder retains its formative power. The American philosopher Martha Nussbaum, in her work on the emotions, observes:

Wonder is the basis of respect. Without wonder, we become morally numb.

Thus, wonder is not just an intellectual start—it is a moral awakening. It undermines the illusion of mastery and reveals the inherent dignity of others and the world itself.

If wonder is where philosophy begins, then it also resists finality. And in that refusal to conclude, it opens up a deeper form of knowing.

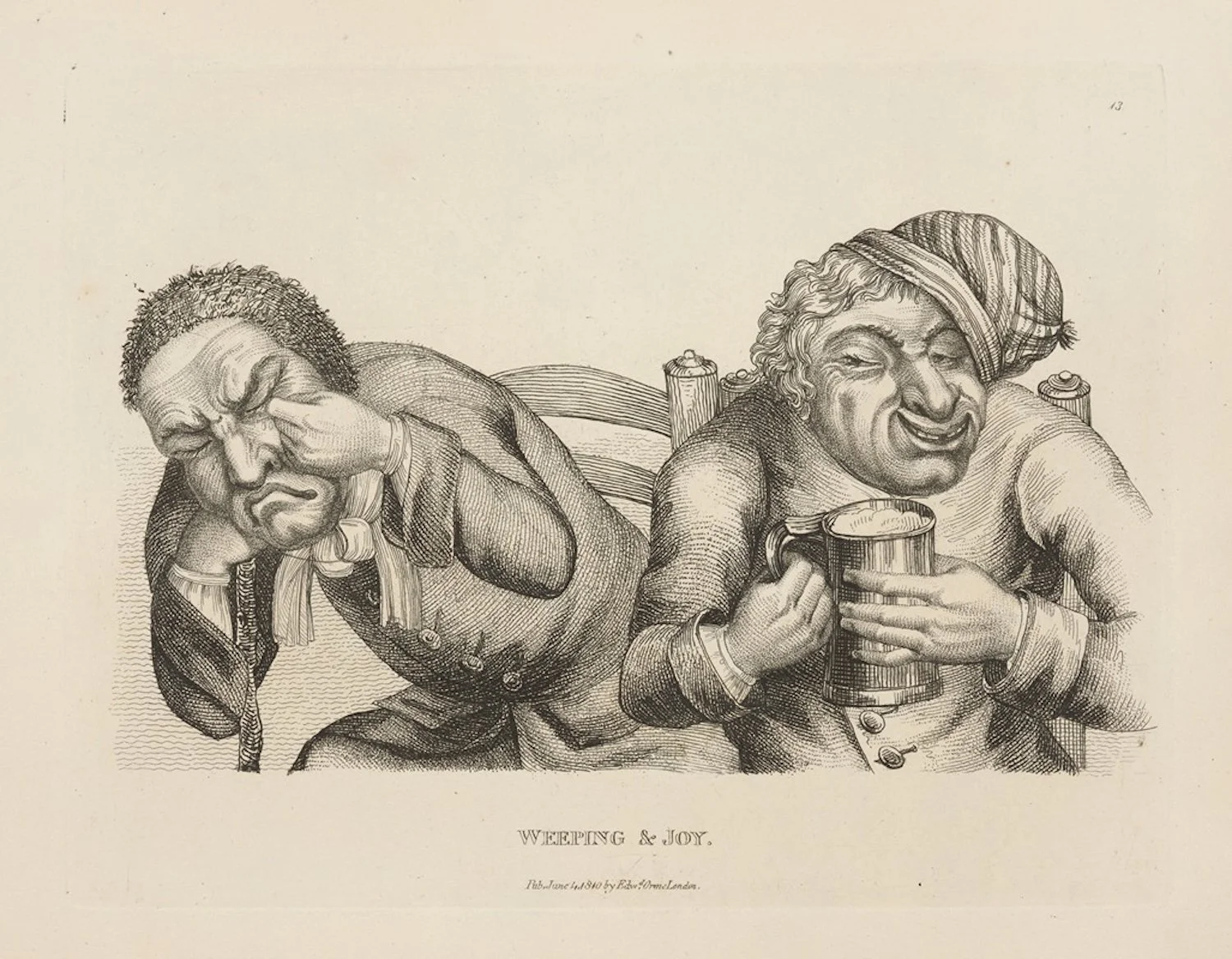

Two Poor Men Sleeping by Isidre Nonell (1897)

2. The Art of Knowing

Wonder is frequently misinterpreted as the opposite of knowledge, viewed as childish or irrational. However, numerous philosophers and psychologists contend that wonder is not a rejection of understanding but rather its most profound source.

In contemporary scientific terms, to know something typically means to define, predict, or control it. In contrast, wonder defies such simplification. The French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain suggests:

To wonder is not to doubt. It is to be amazed at a mystery, fully real, that one feels is intelligible though beyond one's grasp.

In essence, wonder is not simply ignorance; it reflects a deep reverence for an intelligibility that surpasses our ability to fully grasp it.

Philosopher and theologian Rudolf Otto, in his exploration of the divine experience, called this the mysterium tremendum et fascinans—a mystery that simultaneously captivates and overwhelms us. While he focused on the sacred, his insight resonates with all instances of wonder.

Even modern psychology supports the idea that wonder represents a refined form of attention. In his research on awe, Dacher Keltner proposes:

The feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world.

His empirical findings reveal that people who regularly experience awe are more generous, more resilient, and more connected to others. Wonder, it turns out, shifts our awareness from a narrow self-focus to a broader sense of interconnection. Keltner adds:

Awe binds us to social collectives and moral ideals. It opens us to new perspectives and new possibilities.

William James, the American psychologist and philosopher, expressed a similar idea more than a century ago. In his work, Varieties of Religious Experience, he referred to mystical and awe-inspiring states as instances of “noetic quality”—an understanding that is felt, immediate, and transformative.

Yet, not all thinkers have viewed wonder in such a positive light.

Friedrich Nietzsche cautioned against wonder as a form of self-deception—a refusal to confront the raw absurdity of life. Albert Camus similarly perceived wonder as the moment before one comes to recognize the absurd.

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus stressed:

At any street corner, the feeling of absurdity can strike any man in the face.

Yet, even Camus, profoundly committed to clear-eyed rebellion, couldn’t overlook the strange beauty of the world. There exists a delicate line between wonder and illusion—but it’s a line worth exploring.

In this way, wonder offers a kind of understanding that deepens rather than resolves the issue. It doesn’t close the world off but instead opens it—and us.

Disappointed Soul by Ferdinand Hodler (Public domain)

3. Wonder as a Way of Life

If wonder is the beginning of philosophy and a mode of knowing, it is also a way of life—an attentiveness that can be cultivated. Many religious and contemplative traditions have long regarded wonder not as a fleeting mood but as a discipline.

For example, St. Gregory of Nyssa describes the soul’s journey toward God as a deepening into mystery:

The soul’s desire is not to see something definite, but to be always drawn onward, always to be filled with ever greater wonder.

St. Gregory’s vision is not one of arrival, but of infinite ascent—of never exhausting the divine, nor ceasing to be amazed.

Even the philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas, renowned for his thorough approach to theology, concludes his Summa Theologica with astonished silence, stating, “All that I have written seems like straw compared to what has been revealed.”

Likewise, in Buddhism, especially within the Zen tradition, the practice of shoshin, or “beginner’s mind,” embodies this principle.

The monk and teacher Shunryu Suzuki notes:

In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s, there are few.

This attitude is not naive but rather radical—it resists the numbing effects of repetition and keeps experiences fresh. It trains the mind to remain open, free from grasping or judging.

In a world full of distractions, such practices are more vital than ever. Algorithms present us with what is already familiar. We are inundated with information yet rarely astonished. In this context, wonder becomes an act of defiance—a refusal to allow the world to be reduced to usefulness.

Psychologically, this practice fosters a sense of meaning.

Viktor Frankl revealed in Man’s Search for Meaning that experiences of awe—such as watching a sunset or hearing birds sing in a concentration camp—served as reminders of inner freedom for the prisoners.

Frankl writes:

The true appreciation of beauty and nature is one of the last strongholds of inner freedom.

To wonder is to actively engage with the world around us, to joyfully embrace the mystery of life. It’s not about sitting back and doing nothing—it’s about being fully present and alive to every moment.

As the American poet Mary Oliver succinctly reminds us:

Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.

At the Window by Peter Listed (Public domain)

Final Thoughts

Once more, wonder is not an evasion of reality but a committed return to it. It embodies a perspective that declines to yield to cynicism or simplification. In a time fixated on speed, control, and certainty, wonder signifies a subtle revolution.

We begin with wonder, and—if we are fortunate—we return to it repeatedly. It slows us down, opens us to new ideas, and reminds us that the world is more than a problem to solve.

Living in wonder involves striving to appreciate the mystery of being human. It means dwelling in the mystery of existence without rushing to closure.

It is to live, “not in the measurable and the useful,” as Søren Kierkegaard writes, “but in the eternal and the essential.”

Reflection Exercise

Take a moment to ponder a time when you experienced a genuine sense of wonder. You might also consider one (or all) of the questions below:

When was the last time you experienced that delightful feeling of astonishment from something ordinary?

Imagine how your daily life could transform if you embraced routine experiences with the perspective of a “beginner’s mind.”

In which parts of your life do you feel you’ve swapped wonder for certainty, and how can you regain a sense of mystery and awe?

Daily Meditations

“Never stop learning how to live!” Join our email community today by subscribing to Perennial Meditations (on Substack). There you’ll gain access to our meditations, podcasts, and courses.